Gunning for Daylight: Meditations on Depression and Storm Above the Reich

Over winter I learned a lot about myself and Storm Above the Reich from GMT Games

If you’d rather hear this than read it, check out Episode 86.

I had to treat 2023’s two-month run of nightly suicidal ideation with some skepticism. In 2022 I daydreamed about it for three days because my job was boring.

While detailed — my garage, a stepladder — it lacked sufficient motivational agony. The view through that escape hatch solved itself when I went deep field. Oh, look. There’s me being found by my neighbors’ grandkids. Poor form.

I still had to ask: “Where is this coming from? Why so appealing? Why so often?”

Aside from what was likely some kind of major seasonal depression, thinking about snuffing it gave me a sense of power and relief. Everything since 2019 had felt like the same long year. 2019 was when bad habits and bad breaks finally got on the phone and started coordinating with my warehouse of unattended personal work. It was a hell of a collab. Eject switches glowed disproportionately.

Everything from unanswered emails to the gradual, silent burial of general indifference had twisted my mind. My God, the amount of tribunals I conducted during the average day, alcove after alcove of defendants spiraling in a tower up to the hell of my skull. I restarted and won several fights from years ago in the course of any given minute.

I clawed my way to the 17th of January in this fashion. That’s when the gloom lost its density. It was still cold, but the evening light was counterattacking. Minus the hateful business of the holidays, the deep winter tipped to the sweet, the simply quiet, the restorative.

This was when I decided to burrow into Thunderbolt Apache Leader. I’d learned to use these kinds of tools before. But as the biographies show us, you can have the talent, the workspace, the instrument sitting right in front of you and not even have the will to pick it up and play a single note.

But I got the damn box open and started slogging through the rules. It was on my table for something like seven weeks before I could run a turn without having to look at the rulebook every step.

Not only did it finish off the gloom, it replaced it with a different world. I balked at the early pages of the rulebook. But I pushed through until I found myself capering across the high-gloss terrain hexes, running mission after mission, ecstatic.

I’ll never forget the day it deposited me on the other side. It was March. I’d opted for some dark beers and yet another mission on a Friday evening. I’d been hunched over the game every possible minute that week. It was well past six p.m. and I found myself standing in a shaft of warm evening sun that would not dissipate. It was just hanging there over the ridge. I’d found a friend for winter’s last mile and I’d made it. I’d made it, and I knew how to work that board like an air traffic controller. One at a pokey regional airport, but still.

Is There A Lightning Refill Station for This Bottle

It’s facile to say that Thunderbolt Apache Leader saved my life. Patience, time, minor rearchitecting of habits and a bit of self-reflection did that. But the game was an alchemical accelerant.

So was peeking over the fence into the hex-and-counter boys’ backyards. I started relaxing at night to videos of other middle-aged men with single-shot videos and uneven audio and lots of regimental tattoos in their intro music — the less polished and more avuncular, the better — who played chunky historical wargames.

A lot of these guys were my age. And chummy. And not worried about being cool. They were an after-the-fact proxy for the Saturday night basement crew who adopted me socially — and who I rejected — in middle school. They appeared on forums with well-cited answers to rules questions or cheered along with you when you emerged from a scrap with a clever new tactic. They made their own systems of markers and spreadsheets to customize their workflows. They had medical tweezers to move counters around so they didn’t bump the little stacks in neighboring hexes. If you told me I could have spent the next 100 Saturdays drinking beer and hollering at bum artillery rolls in a big table in a garage with some of these cats, I would have done it.

Dozens of videos and reviews gave me the taste for more war- and empire-themed stuff. By midsummer 2024, I had a strategy and a shopping list: Storm Above the Reich, because I wanted to see a different flavor of air war game and the scope — building and managing a squadron, commanding missions and tracking their minutia — seemed similar enough to Thunderbolt Apache Leader; Hadrian’s Wall, because it simply looked arousing and fussy and unlike anything else on my shelf; and Pavlov’s House, which became an idée fixe early in my reading about DVG’s Valiant Defense series.

If TAL provided such a lift, then loading up on three chewy titles would turn the darkness away for even longer.

I started with Storm Above the Reich. My parents visited in early October for my birthday. I got the solid work table and four matching stools I wanted as my primary dining set and play surface. I could then use my folding table as an auxiliary learning space so I wouldn’t have to pack the game away for meals I couldn’t wolf over the stovetop. I got Storm out on the folding table the second week of October. 90 days later it was still there; I’d barely played one mission.

It didn’t work.

November beat me again.

Unboxing Storm Above the Reich: The still-gentle days of October, when anything felt possible.

Learning Storm Above the Reich: The Impenetrable Double Membrane of Chatty Rulebooks and Paralyzing Sadness

I like the dramatic proposition that Storm Above the Reich puts before me. What I don’t know is whether I can pierce the double membrane of depression and the administrative burden of this system.

I smell an action and story payoff in the game’s cycle of picking planes, positioning, approaching, attacking, and getting shot up at various points along the way. But between this experience and me is a cowering numbness, a refusal bordering on panic when I realize my brain doesn’t want anything new. I crumple on each new page. My eyes move over the diagrams, seeing nothing. I overeat processed foods — anything to feel full with little effort — and spend evenings watching anything on YouTube that kills the hours. I pick movies for their running time.

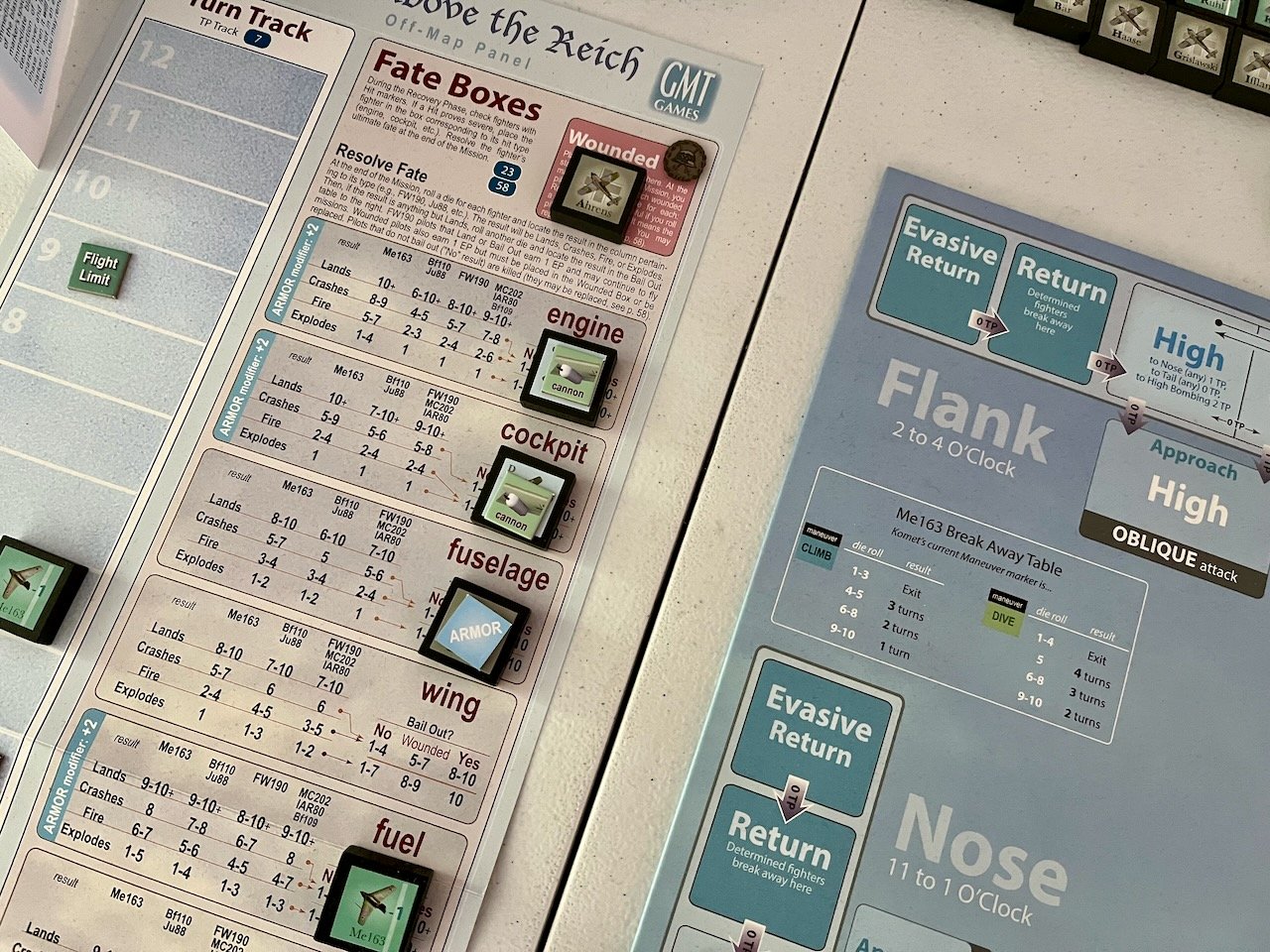

Storm Above the Reich (GMT Games) is the second installment of a (so far) three-game series of designs from Jerry White and Mark Aasted that zoom in on the experience of managing WWII-era fighter squadrons as they try to make dents in wave after wave of incoming bombers. Like a lot of challenging solo games, the aim of the thing is to turn the feeling of being totally screwed into a forkful of moist seven-layer debacle cake.

And because it’s historically modeled, the Luftwaffe were pretty screwed when the Americans fired up those assembly lines; tapped its endless supply of sturdy, pissed-off kids with good eyesight; and got the bomber wings rolling.

The first game in the series, Skies Above the Reich, lets you try your luck in single-mission or campaign mode flying Messerschmitts against B-17s. The third and newest, Skies Above Britain, sees you scrambling RAF fighters against the Germans as they try to batter the UK to its knees. In Storm, my charge is to fly Focke-Wulf 190s against B-24J Liberators and all their deadly helpers, which include Kittyhawks, P-38 Lightnings, and God forbid, Mustangs.

If you don’t get picked off by those, your reward is diving into a formation of B-24Js flying in combat boxes, bristling with .50 cals and fairly snug in their overlapping fields of fire. You hope to harry the bombers enough to degrade their formation and maybe even shoot one or two down. (In case the havoc on the main board isn’t enough, there is an advanced variant in which you can find out what happens when your fighters break out in pursuit of an isolated quarry.)

The historical and day-to-day variables are painted in dozens of hues: The kind of mission you’re going to experience will morph based on which year it is. 1943? You’re somewhere over the Mediterranean and you can spend points to bring Italian fighters along. You’ll have more experienced pilots. 1945? You’ve still got the planes, but a dwindling amount of kids who can fly them off your makeshift fields. The escorts are deadlier and more numerous. The bomber formations are bigger and more disciplined.

A ton of d10 rolls during setup abstractly present the wild variance of the battlefield overhead and your intercept readiness. Some missions you can only scramble a fistful of planes. Is the incoming wave on approach, over the target or on their way home with empty bomb bays? Where is the sun? What kind of fighters are supporting them and how many? Is the formation high enough to throw contrails? Did the Americans have to rush a damaged bird or two out? Which ones are hit and how badly?

Against this richly rendered picture, you enter into a give-and-take of decisions and determinism, tap-dancing in a seam of agency through a field of attack, escort, breakaway and damage resolution tables. Spend your points. Pick your approach — flank, nose or wing. Decide whether the pilot is Determined (that MFer isn’t going to fire until he can count the side gunner’s freckles) or Evasive. A pilot with Evasive disposition fires at greater distance and incurs less chance of being hit, but burns more time getting back into position for another run, also creating more exposure to American fighters that peel out of their bunched trailing positions to stalk you.

Every flavor of fix you’re in has a rationale, a pedagogical thrust. Which I know because the rulebooks’s authors don’t let you forget about it once across 50+ pages.

This brings us to the inseparable aggravation and charm of this system. Storm Above the Reich is profuse and prolix, both in voice and documentation. Even when I’m not “getting it,” I delight often at brushstrokes like these:

“Map 8 represents a combat box of late-war B-24 heavy bombers. Each is armed with a third gun turret mounted under the nose, a ‘chin turret’ intended to punish Luftwaffe pilots attacking head on. The formation by 1944 had become a cauldron of spraying tracers.”

Or this, inserted into the instructions that guide you through how to simulate the behavior of Allied escorts:

“There are other bombers nearby as well as other Luftwaffe fighters, so if it seems an Escort marker is just sitting there doing nothing, it may be because their attention is elsewhere. It could also mean that they are low on ammunition, low on fuel, are following orders, or their pilots simply do not see your aircraft. It’s a big chaotic moving battlefield and maybe somebody besides you screwed up for a change.”

This narration features prominently across the book, loquaciously interjecting between the procedural, the abstracted, the implied animal adrenaline, the sweep of history and the fortunes of the day.

This voice also welcomes me in the sparsely-traveled alleys of the game’s forum on BoardGameGeek. The profile name of the guy with the best rules answers seems familiar. I check the side of the box. It’s one of the designers, Jerry White, the patient uncle who can’t resist a story or an explanation. (I record and speak to others like this often; I recognize the impulse.)

He shows up more than once to nudge me out of the wilds of uncertainty and back onto the board, with its repeated patterns of light grey bombers on flat sky blue. Its tones remind me of the patterned wallpaper I’d trace with my hands as a kid before falling asleep in my grandparent’s spare room over the holidays. It’s a voice from the Boundless Board Game Saturday Night, feet on shag carpet, a recent starchy meal still in the air, bedtime far away.

I don’t think I would have gotten through my first few turns without Jerry (and the dudes who landed on the BGG forum as confused as me). Storm Above the Reich frequently dares you to understand it. The info hierarchy, the typography/color choices on the books and counters throw me a lot. So here is an aid with an Operations Menu on the cover, labeled as Step or Phase J of a mission. OK. I look inside the four-page card: The inside left page is labeled G: Instructions. Explanatory callouts reference incorrect pages. There’s a master turn sequence printed on the board, but it’s at the lower left in what looks about 12-pt. white type and there’s a lot of competing info on the board: flavor quotes, scenario-specific explanatory paragraphs...these boards have been asked to do a lot. Sometimes it all looks like a palimpsest of a prophet cross-talking with generations of breakaway sects.

Is it November or December, taking it in such small bites that I can scarcely carry over what I’ve learned from the last fidgety sit? Some linearity starts to emerge from the insane pile of cards, counters and boards.

Why am I like this? Why is each of these things a new universe? Why is my mind such a piece of shit? Why can I write this, but not be, like, a person? Aren’t there any middle gears?

My favorite is curling up at night in the enclosing drey of sleep meds, hitting in stages as Toby Longworth reads to me about a hive city getting shelled. As I tug the voice on the speaker to the foreground, I close my eyes and see myself as an outline with moth wings, dead man’s pose, a faint stroke of grayscale around me, rising up to the succor of inexhaustible black.

Some Me163 experimental jet jockeys pitched in, but one’s out with a fuel tank hit and the others have been scattered to the four winds. That leaves two other FW109 kiddies whose planes aren’t shot up, but they got intercepted on their approach and pulled into a dogfight by two Mustangs. I’m not sanguine about their chances.

First Mission: Let’s Do This In the Most Difficult Way Possible

Relax, you freak, and read it again. Now just write down your staffel info like it says in the book.

Pops once warned me about the males in our bloodline and their attraction to doing everything the hardest way possible. I wasn’t listening. I decide to learn on a mission that’s set in 1945. I walk the setup steps: I’m dispatched against 27 B-24J Liberators — shadowed by a complement of hungry P-51 Mustangs — inbound to a German target. Because it’s late-war, all my pilots are about 14 years old.

I take three up-armored FW190s, three other FW190s with upgraded guns, and four fast, but mercurial, Me163s—right up the trailing bomber element’s asspipe, because the setup indicates they are throwing contrails that my flyers can use for cover.

I don’t want to try attacking from every angle on my first run, so I rush everything I have at the tail of the formation, luckily avoiding collisions with my own craft. The Me163s and FW109s succeed in knocking the tail bomber out of formation and inflicting three points of damage on another. One Me163 is now out with a fuel tank hit — I assume this guy is going to be a comet of burning fuel in about .03 seconds. The other jets are scattered to the four winds by Mustang swarms running interference. Of the FW109 rookie wave, Ahrens is shot down and wounded. Clausen takes a heavy hit to his engine. Doppler and Ehlers? Heavy hits to the cockpit and fuselage, respectively. Zick and Oesau get intercepted on their approach and pulled into a dogfight by two other escorts.

The plan is to be well in my cups by the time they die en masse so I can focus on listening to the Psychedelic Furs and staring at that one streetlight down the dirt lane that focuses the middle ground and distracts me from the first of two derelict houses on my property that were supposed to be a toehold on some kind of empire. I need simpler plans, like music and beer.

What I know of the rules is as tenuous as the line I can trace from my streetlight to the neighbors’ to the distant third on the two-laner. It’s OK. Track seven of Talk Talk Talk is up: “It Goes On.” How was this band so good? You can bail out of a plane and land in this song and ride it through the night.

One Thought Can Take a Season of Your Life

I was talking to dudes on BGG’s Squad Leader forum about the copy of the game that The Moms got me for Christmas in 1979. She knew I was into WWII history and war movies, because weren’t we all?

I was 10. I opened it, gawped at each bit of it, and put it away. Maybe my best friend Jesse could have played it with me. We would have had all of middle school to argue about it on the weekends. But we never did. We ended up moving to the same state as teens, but never re-established the Missouri bond. He died on Facebook. And some of the dudes on the BGG forum mentioned a common denominator: “My big brother and his friends…” They got to learn it under the wing of some adolescents.

And I realize it doesn’t matter how cool these games are unless somebody is there with you, moored at the point of fascination and raised on the broth of brotherhood. And I stopped shopping a bunch of wargames I liked that YouTubers were talking about when I realized I wasn’t shopping for a game. I was shopping for a big brother I never had, or friends I had and don’t have anymore. I thought it through, like I had my visions of eliminating myself, and thought better.

I have to be my own big brother now. I’m a solo player. It’s a lot of goddamn work, raising yourself all over at age 55. The great poets provide hints. Intuition sows fertile blanks between embarrassments. The lack of applause at the checkpoints is appalling.

Try-N-Fly: Mission Two

I try again in mid-January. Sunset is gradually creeping up to that 5:00 mark again, I know because I track it on the weather apps every week. There’s a smear of painfully bright indigo on the western ridges across the highway that wouldn’t have been there two weeks ago.

I set aside a whole Friday night. I let a wall of flame wash over the to-do list. And I still buck at the threshold: Just admit you bought the wrong game, dude. You’re forgetting your own rules: If you continually have to ask yourself if something’s worth it, that’s your answer. You burned $90. It happens. Let it go.

But I march to the table anyway because I don’t entirely trust the guy in my head who told me last month I couldn’t figure this game out. We’re going in again.

This time I start with the very first mission: 1943, the sunny Mediterranean. I pour a nice stout and keep the Golden Era beats perched on the edge of the sonic midground. Just do the turn, I tell myself when I want to drift away and harangue old friends on VoIP. Do the damn turn, you big, sweaty diaper.

Ehlers attacks solo on the first mission in an unmodified Focke-Wulf with two Italian pilots nearby in their MC202s. I conduct the planes in a fluid loop at flank attack angles for six turns of a Near Target scenario, making a mess of the formation’s middle element. P-40 Kittyhawk escorts appear briefly and are easily dodged before they melt away. Ack-ack takes divots out of other elements in the formation.

I finally see the coherent game cycle previously occluded by The Black Dog. The Magic Circle has enough surface tension to sustain itself. Another good sign: I’m bellowing at my aircraft in between runs. “Well, are we gonna get these motherfuckers or what?”

I back my way into a personalized workflow through the reference cards, books and board data. I discover and fix several small things I was doing wrong. I’m running more of the turns using just the abbreviated instructions from the reference cards instead of plowing through the book every step.

I land the craft, make some hashmarks on the mission log with a pencil. Put a dumb, loud song on repeat until I pass out, get out of bed and walk straight to the table the next morning. This cold snap is brutal, but there’s just enough of a suggestion of Something to Look Forward to. Marked against last year, I have gained a playable picture of a daunting new game nearly a full month earlier than last year. It did not salvage November and December, but I note the improvement.

Is There a Future With My Jocund and Bulky New Pal?

Yes. I can tell because I get enough of the mechanics repeating until they generate a luminous still from the movie I sensed on the other side. It is light painting, alive and effective and satisfying even when the story doesn’t go your way. Take a look at this picture:

This motherfucker right here

This is either a picture of how deterministic game elements bog down a player with a plan or one of the greatest air war short stories ever. I rake this single B-24J with high-altitude Oblique and Nose attacks for nearly six turns. I can not force him out of formation. I become livid, fixating on taking him down. Half of his crew must be dead or hit. I pepper the fuselage, engines, the wings, and he’s still magnetized to his three-plane element.

Whoever sits at the controls of this bomber is the most adamantine West Point product in the history of the institution. Some days you will simply bounce like a pebble off the aura of Jupiter’s adopted son and there’s nothing you can do about it, which is one of the brightest threads of Storm’s weft. This most of all: An initially cumbersome machine that belches out its own beguiling gems if you keep turning the crank.

Will I play it again? Yes, although in my dilettante’s eyes this game was difficult, tangential, unwieldy, self-indulgent and baffling — moments of cerulean evocation and constricting pace. It’s a weird niche product. But so am I.

It also feels like a successful bid for entry into the Fellowship of Crunch, resonating with my need to seek, handle and celebrate things whose justification is brighter the farther they are from the digital braying of this putrid age. The little work of the movements, planes trailing caravans of cardboard modifiers, are the ghost notes of the most endearing fans’ war songs. At both its most gripping and frustrating, it smacks of vellichor.

A minute tilt of the seasons can throw you from the planet’s surface. A bad run spiderwebs the canopy. Ever toward the sun, fuckers. Unless a sun position is indicated in the Situation Manual, in which case you keep that shit at your back because the .50 gunners on those B-24Js are not there to cheer you on.

Learn to Play Storm Above the Reich: Get Rinsed in a Brawl at Staffel Haus

Well, that squadron didn’t last long: Notes from my rookie attack run in the WW2 air war game, Storm Above the Reich from GMT Games.

I like the dramatic proposition that learning Storm Above the Reich has put before me. What I don’t know yet is whether the action and story payoff is equal to the administrative burden of running it.

Of course, I’ve done this the hard way: Randomly selecting a mission to learn on and drawing a scenario in which 27 B-24J Liberators—shadowed by a complement of hungry P-51 Mustangs—are inbound to a German target. Since the scenario’s set in 1945, all my Focke-Wulf Fw 190 pilots are about 14 years old.

I didn’t want to try attacking from every angle on my first run, so I rushed everything I had at the tail of the formation, luckily avoiding collisions with my own craft. The Me-163s and FW109s succeeded in knocking the tail bomber out of formation and inflicting three damage on another.

I’ve run three turns of the first mission: Ahrens is shot down and wounded. Clausen has taken a heavy hit to his engine. Doppler and Ehlers? Heavy hits to the cockpit and fuselage, respectively. An Me-163 sustained a fuel tank hit, so I’m going to go ahead and assume this guy is going to be a comet of burning fuel in about .03 seconds.

Some Me163 experimental jet jockeys pitched in, but one’s out with a fuel tank hit and the others have been scattered to the four winds. That leaves two other FW109 kiddies whose planes aren’t shot up, but they got intercepted on their approach and pulled into a dogfight by two Mustangs. I’m not sanguine about their chances.

I think picking this Storm Above the Reich 1945 scenario to learn on was the equivalent of walking right up to the most crowded table of meanest dudes at a Waffle House after the bars get out and just spitting on their table.

Look for deeper impressions—and hopefully a semblance of air command competence—in a future episode of Breakup Gaming Society.